CoreWeave Redux

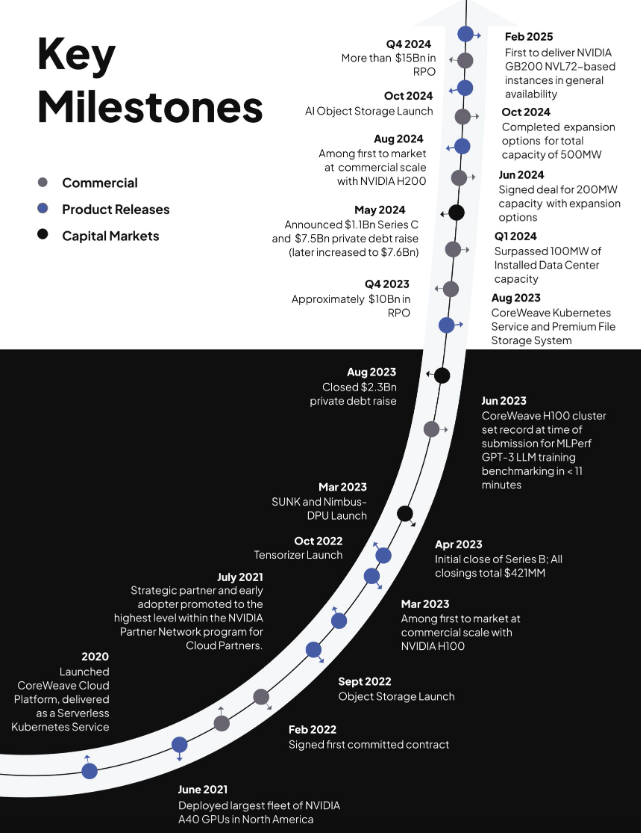

CoreWeave dropped their S-1 on March 3rd, making it one of the first AI-wave companies to file for IPO (Cerebras might postpone IPO plans due to CFIUS review over their G42 deal). I say AI-wave company, because not too long ago they were a crypto company offering GPU rigs for mining bitcoin, who pivoted to fulfilling AI demand after crypto cratered in 2019. They pivoted so hard, that their crypto past doesn’t even show up as a key milestone.

Source: S-1

Source: S-1

It’s a uniquely interesting company as it’s core business is renting out 250,000+ units of what might be one of the fastest depreciating hardware assets in recent times on its balance sheet. This massive GPU fleet represents both CoreWeave’s greatest strength and potentially its greatest vulnerability - and this makes their S-1 particularly worth examining.

Some stray observations:

Explosive Growth

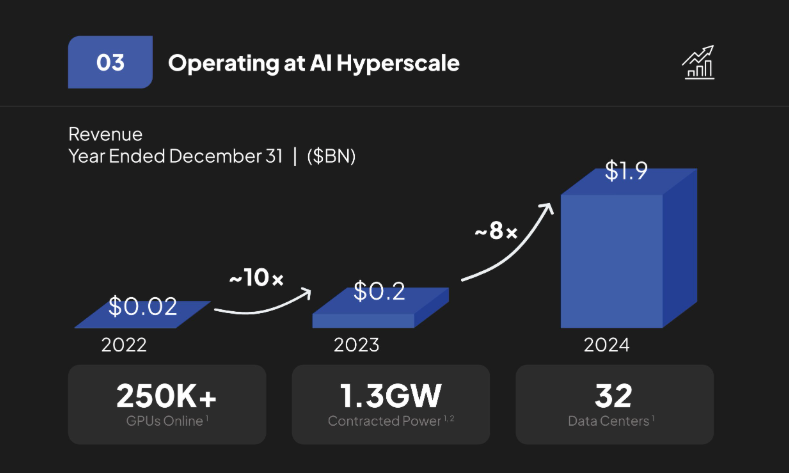

Source: S-1

Source: S-1

That’s 737% in revenue growth from FY23 to FY24 and a CAGR of 875% from FY22 to FY24. These numbers are bonkers enough to warrant a deeper look. Byrne notes:

The sample size is small, but striking: companies that set revenue growth rate records, like Compaq, Zynga, and Groupon, often do this because they can scale fast on somebody else’s platform. Compaq was the fastest company ever to reach the Fortune 500 list (four years after founding). It built IBM-compatible PCs using Microsoft’s OS. Groupon was founded in 2008 and hit $713m in sales in 2010. It grew by voraciously paying up for leads on Facebook and other digital channels. Zynga had a similar trajectory; it was founded a year earlier, and hit $579m in sales by 2010. Zynga, too, used Facebook. In their case, it was Facebook’s platform and organic social features, more so than ads, that made Zynga’s model work.

Companies that build durable businesses grow more slowly, and there’s a reason: Compaq, Groupon, and Zynga all figured out their unit economics quickly, and because they were interacting with large platforms, they could scale arbitrarily fast. Once Compaq knew how much it cost to get commodity PC parts, assemble them, and install Windows, it could multiply that number by hundreds of thousands of PCs and know roughly what kind of profit it could make. And Microsoft and Intel had no trouble producing additional processors or copies of Windows.

The pattern repeats often enough that it might be an economic law: if you can build a company that scales fast by consuming some kind of input that’s a) sold by one company, and b) that appears to have perfectly inelastic pricing, then what that company will do is use its superior competitive position to eliminate your profits, either nicely by charging enough money to wipe out your margin or cruelly by encouraging other competitors to duplicate your easily-copied model.

Build Out

CoreWeave has pursued an asset-light approach to physical infrastructure, leasing all of its data centers and office locations rather than building from scratch. In one of their larger expansion moves, CoreWeave planned to spend $1.2bn to acquire 70MW of data center space from Core Scientific in Denton, Texas. For context, industry estimates suggest it costs approximately $1bn to build a 100MW center from the ground up. CoreWeave’s acquisition strategy reflects both the premium they’re willing to pay for speed-to-market and the intense competition for AI-ready infrastructure with sufficient power capacity. Energy availability is the most critical bottleneck, and CoreWeave seems willing to pay a hefty premium.

On the chip front, CoreWeave faces a single-supplier dependency. With Nvidia holding a 5% ownership stake and providing all 250,000+ of CoreWeave’s GPUs, their negotiating position for hardware pricing is severely constrained. This arrangement gives Nvidia significant influence over CoreWeave’s unit economics while simultaneously benefiting from the company’s rapid expansion as both a supplier and investor.

CoreWeave’s $15.1bn in Remaining Performance Obligations necessitates scaling infrastructure at a breakneck pace to support $3.8bn in annual revenue over the next four years—nearly twice the firm’s revenue in FY24. Whether they can lease sufficient capacity fast enough (and at tolerable rates) will be the make-or-break factor in delivering on those contracts.

And all of this assumes that the contracts remain in place, which not happen given reports of Microsoft pulling out of contracts with CoreWeave. What’s more troubling is that MSFT’s withdrawal doesn’t merely reflect Satya’s view that there’s been an overbuild of AI systems but instead appears to stem from CoreWeave’s operational performance. From FT:

However, Microsoft has withdrawn from some of its agreements over delivery issues and missed deadlines, according to people with knowledge of the matter.

While those people declined to discuss specific details about the abandoned services, one of them said the issues had an impact on Microsoft’s confidence in CoreWeave.

Microsoft isn’t just any customer — it’s the largest customer of CoreWeave (62% of FY24 revenues) and losing their confidence could have ripple effects throughout the industry.

Unit economics

Byrne published an excellent analysis on the unit economics of CoreWeave:

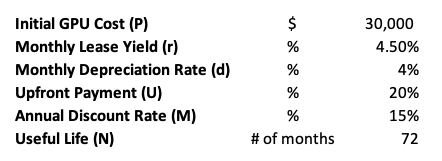

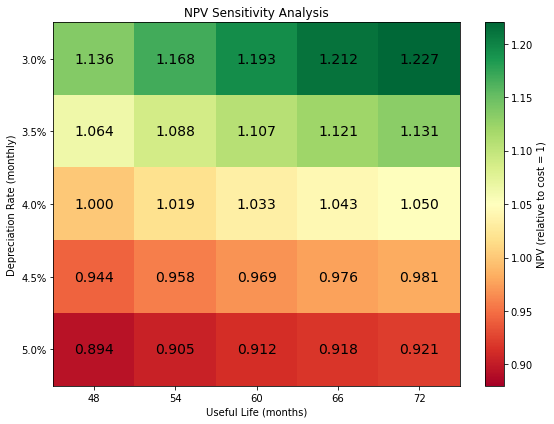

So we can walk through some illustrative economics. CoreWeave breaks even on a roughly cash basis 2.5 years into their purchase. They say that customers pay 15-25% of the contracted amount upfront. We can bake in a decline in GPU prices over time—this hasn’t happened all that much based on the datapoints that are publicly available, though older chips do tend to decline in price. If you assume that GPUs initially get leased at a price that produces a 4.5% monthly return on assets, and that their prices decline around 4% monthly, you get to the 2.5-year breakeven that CoreWeave is talking about. (It’s hard to get to their numbers looking at published hourly GPU prices. There’s some mix of discounts for committing in advance and lower-than-100% utilization, but it’s hard to know which.) In that model, the present value of a GPU’s cash flows, discounted at 15%, is 5% higher than their upfront cost. But 15% is actually a low number for their hurdle rate, given that they have borrowings at rates as high as 14% for credit lines. (They have some convertible debt with a higher effective rate, and pay a lower rate — 9-11% on vendor financing

Now I’m not Byrne, so this math isn’t obvious to me. Excel is my weapon of choice so let’s walk through that:

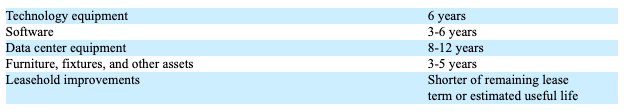

The H200 chip costs about $30,000. Monthly discount rate (\(m\)) comes out to \((1+0.15)^{1/12} - 1 \approx 1.2\%\), assuming a 15% hurdle rate. Let’s assume a depreciation period of 6 years (72 months) as CoreWeave does.

At month 0 (time of purchase):

CRWV receives an upfront payment of \(U \times P = 20\%*30,000 = 6,000\)

At month n = 1, 2,…N:

CRWV receives monthly lease payments. Each month, the GPU’s book value will depreciate. So for month \(n\), the GPU’s book value at the beginning of month is: \(\text{Book Value}_n = P \times (1-d)^{n-1}\). Thus, the lease payment for month n is: \(\text{Payment}_n = r \times P \times (1-d)^{n-1}\).

CRWV reaches breakeven when:

or

\[P = U \times P + \sum_{n=1}^{N-1}{r \times P \times (1-d)^{n-1}}\]Solving for N gives ~30 months or ~2.5 years. And if we want to calculate the NPV:

Each monthly payment is received at the end of month n and is discounted using the monthly rate m:

\[\text{PV}_n = \frac{r \times P \times (1-d)^{n-1}}{(1+m)^n}\]Thus, the sum of the discounted monthly payments over N months is:

\[\text{PV}{\text{months}} = \sum_{n=1}^{N}{\frac{r \times P \times (1-d)^{n-1}}{(1+m)^n}}\]After plugging in the values,

\[\text{PV}{\text{months}} + \text{(discounted monthly sum)} \approx 0.20 + 0.85 = 1.05\]So the investment has about 5% in NPV over the lifetime of the GPU, while assuming a 15% hurdle rate. Given effective interest rates on their loan facility go up to 15%, it’s possible that their hurdle rate is even higher, leaving less room for value creation.

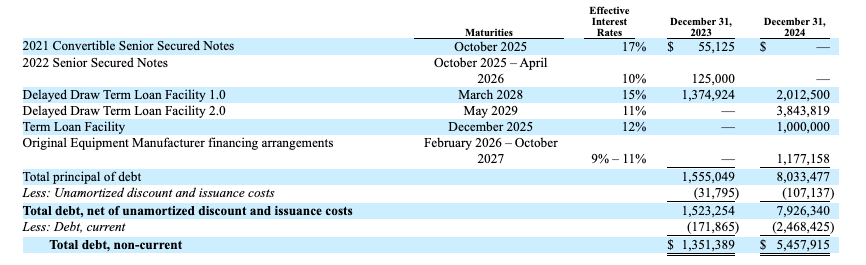

Source: S-1

Source: S-1

Sensitivity to depreciation period

CoreWeave’s entire business model revolves around buying expensive GPU hardware and renting it out over time. The faster these assets depreciate (either through accounting methods or actual obsolescence), the quicker they need to recoup their investment to maintain profitability. Currently, CoreWeave assumes a 6-year useful life for its chips, up from 5 years in 2023.

Source: S-1

Source: S-1

For comparison, in early 2024, Amazon extended the useful life of its cloud servers by one year to 6 years. And in one year, they have rolled the period back to 5 years (for a subset at least). From Amazon’s Q4 2024 earnings call,

First, in Q4, we completed a useful life study for our servers and network equipment and observed an increased pace of technology development, particularly in the area of artificial intelligence and machine learning. As a result, we’re decreasing the useful life for a subset of our servers and networking equipment from six years to five years, beginning in January 2025.

This isn’t just accounting minutiae - it’s Amazon acknowledging that AI hardware is depreciating faster than traditional server equipment. If we apply this same logic to CoreWeave and shift from 72 months (6 years) to 60 months (5 years) on an NPV sensitivity chart, their NPV ratio drops from 5% to 3.33% even if depreciation rates remain constant.

The situation becomes even more precarious when we consider Nvidia’s accelerating innovation cycle. The H200 chips that CoreWeave is deploying today could face competitive pressure from future Nvidia chips. Unlike traditional cloud providers who can repurpose aging servers for less demanding workloads, AI-optimized hardware faces steeper performance cliffs compared to newer generations.

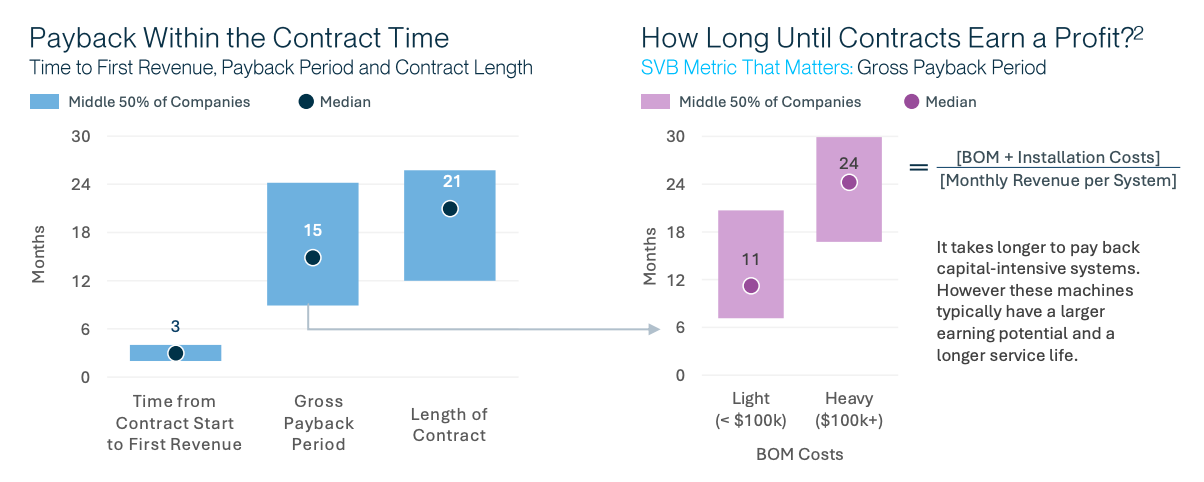

Payback period

CoreWeave’s stated payback period of 2.5 years appears significantly longer than industry benchmarks. A report from SVB suggests that the median payback period for Hardware-as-a-Service companies stands at just 15 months.

Source: SVB

Source: SVB

While not a perfect comparison (CoreWeave’s GPU-intensive model differs from typical HaaS), this gap raises questions about capital efficiency.

Conclusion

CoreWeave’s rapid ascent from crypto mining outfit to AI infrastructure powerhouse is undeniably impressive, with 737% YoY revenue growth and a $15.1bn backlog of performance obligations. However, there are several structural challenges that could threaten the company’s long-term sustainability:

-

The unit economics are razor-thin. With a 2.5-year payback period—significantly longer than the industry median of 15 months for HaaS companies—CoreWeave operates with minimal margin for error. A 5% NPV over a GPU’s lifetime (assuming a 15% discount rate) leaves little room for unexpected market shifts or technological disruption.

-

CoreWeave faces a precarious balancing act between two powerful forces: Nvidia, its sole supplier, controls hardware pricing, while hyperscalers set aggressive market expectations. This squeeze threatens CoreWeave’s already tight margins.

-

Most critically, the accelerating pace of AI hardware innovation presents an existential challenge. Amazon’s recent decision to reduce GPU useful life from 6 to 5 years signals industry recognition that AI hardware depreciates faster than traditional computing equipment. For CoreWeave, each percentage point increase in monthly depreciation substantially erodes profitability.

CoreWeave is attempting to address some of these challenges through vertical integration, recently announcing the acquisition of Weights and Biases, an MLOps/LLMOps player. This move up the value chain could potentially improve margins by offering higher-value services beyond raw compute. However, it also introduces operational complexity at a time when the company is already struggling with execution according to Microsoft’s experience.

The broader context of GPU scarcity monetization and AI infrastructure pricing dynamics helps frame these challenges. While CoreWeave has successfully secured significant customer contracts and financing to fuel its expansion, the question remains whether it can navigate these structural challenges as it scales.