Early Stage

Note: This is a rough draft I’ve had kicking around forever. Finally decided to publish it as-is rather than endlessly tweaking, so this is much rougher than it should be.

Background

All models are wrong, but some are useful.

Recently, a good friend was contemplating angel investing into a pre-revenue climate-tech startup. We launched into a conversation about the market and competitors, attempting to gauge the startup’s potential for success:

…

Me: “The carbon credit market is expected to grow significantly, especially with hopefully increasing regulatory pressure on companies to offset their emissions, given India’s recent commitment to net-zero emissions by 2070.

Friend: “That’s true, but the market already has established, dominant players like EKI. How will this startup will differentiate itself and capture market share?”

Me: “Good point. Let’s try and learn more about the product to begin with…”

Friend: “Shouldn’t we start with the market first?”

…

A little later, I was reflecting on how I could’ve gone about better structuring my thoughts during the conversation. I felt I was being gut-driven and not strictly instrumentally rational in my approach. I possessed some rudimentary knowledge about the field, so I was fairly confident of being able to hold a conversation. Yet, I noticed my weakness in directing the conversation to tackle the right questions: what areas need to be explored, and in what order? How much weight would I place on each area (Product, Market, Team)? What questions should I have asked? How much time should I have allocated to each aspect of the business?

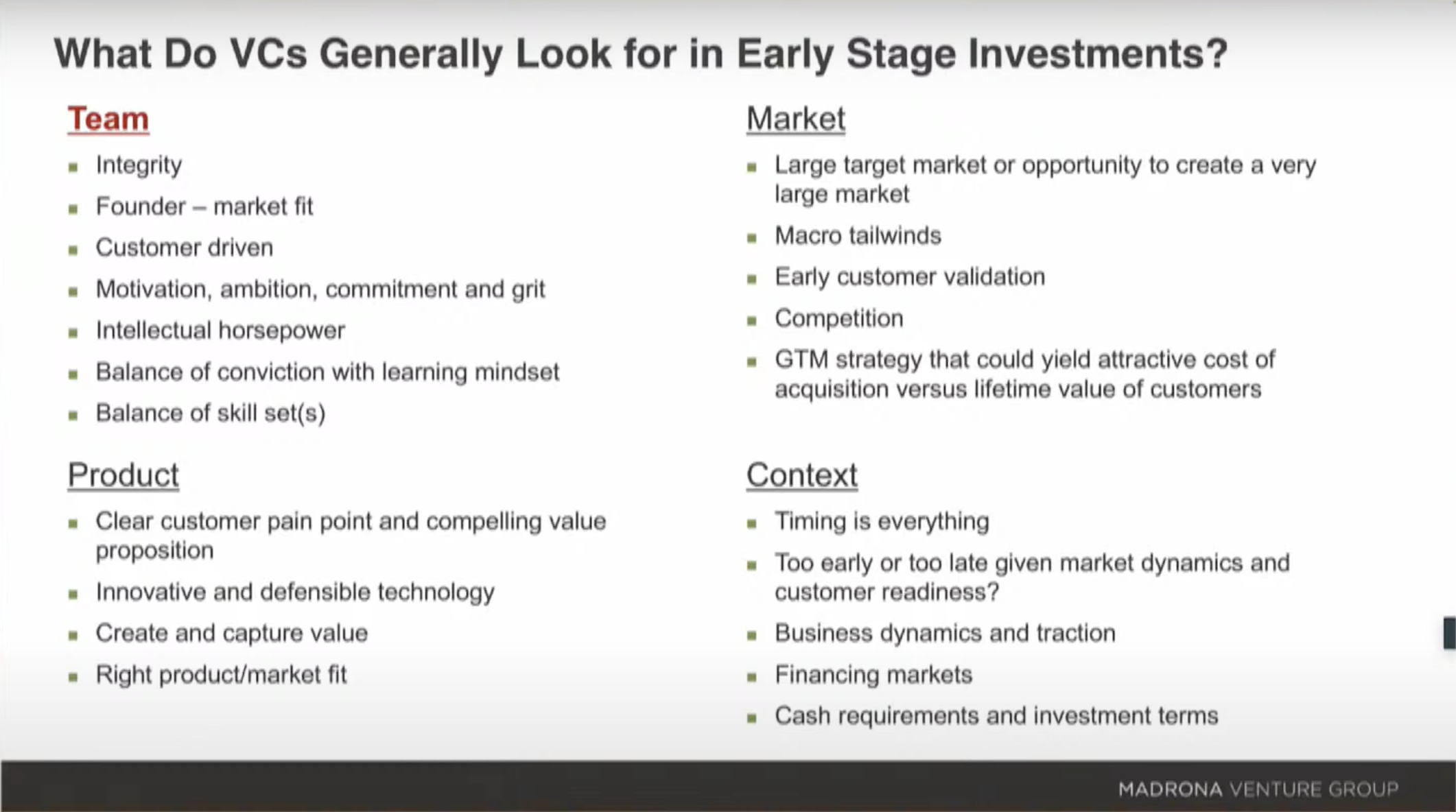

I was familiar with the canonical trifecta of product, market and team, which most firms adopt in some flavour or the other, and I held a few decently informed opinions around them. An exemplary opinion is that the founding team is the ultimate determinant of success, especially in the early stages, with some reputable firms even putting a name to it, calling them “founder bets” — they recognize that the business model, product, and market might change along the way, but the right team will navigate through challenges and adapt. Another is that there’s relative consensus around the fact that a terrible market is a death knell for the most capable of teams and products.

These ideas were disparate and I was looking for a way to connect them structurally. It seemed like an excellent learning opportunity, so I wrote this piece to further elucidate my thinking around early stage investing. I’ve tried to include relatively underdiscussed aspects of each topic (in my humble opinion), because I found it interesting enough to be documented. Okay, enough exposition.

If you had an hour to evaluate a startup, what questions should you be asking?

This is not a definitive guide. This is work in progress.

Outline

- Gestalt - What makes a startup investable?

- Concentration - What’s your investment strategy?*

- Ingredients - What factors shape your first impression?

Gestalt - What makes a startup investable?

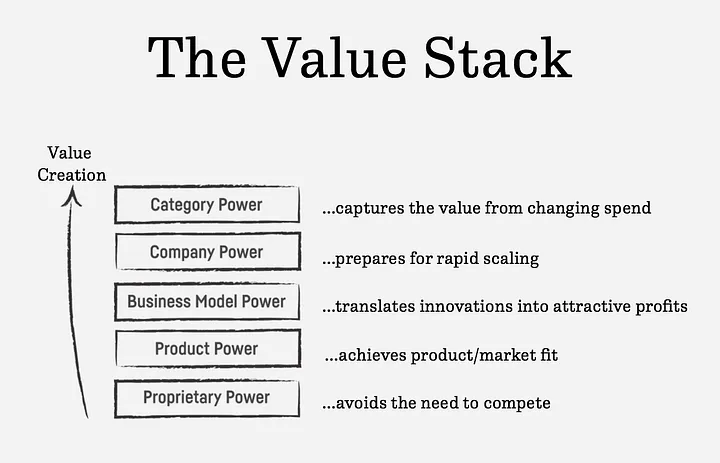

When you’re in the business on betting on tail-end outcomes, it helps to have a notion of what looks like an exceptional tail-end outcome. That sets an effective benchmark for everything you evaluate. Borrowing from Floodgate,

Source: Medium

Source: Medium

Why Floodgate? Apart from pioneering the micro-VC space and being quite successful at it, they are very serious about their startups being legendary (seriously though, the word ‘legendary’ appears 6 times, not including the title, in the 5-minute-read article linked above — they know what they’re talking about). They look for structural competitive advantages that avoid the need for compete altogether, and successively build on it to enable value creation at scale. These are two ideas I’ll expand on in a bit, but as a prelude, the investor’s imagination needs to be focused on a) an existing or possible-to-build competitive advantage and b) a sharp focus on value creation.

Ideally, the combination of product, market, and team should take on a life of its own, resulting from the above two factors, such that a competitor would find it hard to replicate the startup’s success even if they were to copy all three components perfectly. And this is where you want the gestalt principle to kick in.

Concentration - What’s your investment strategy?*

Given power law characteristics of venture returns, perhaps it’s a good idea to spread capital to as many startups out there as possible. After all, the distribution’s mean tends to reach infinity due to tail-end outcomes — some startups achieve such significant success that they can pull the average return toward infinity. If it feels counterintuitive, we’ll come back to this idea in a bit, but it suffices to say that maximal diversification could be a global optima.

Peter Thiel disagrees:

Given a big power law distribution, you want to be fairly concentrated. If you invest in 100 companies to try and cover your bases through volume, there’s probably sloppy thinking somewhere. There just aren’t that many businesses that you can have the requisite high degree of conviction about.

There are several factors that make it an impractical strategy for most investors. First, as Peter Thiel argues, there simply aren’t enough truly high-growth startups to justify spreading your bets across a vast portfolio. Building conviction in a select few companies is more likely to yield the outsized returns investors seek.

Moreover, the challenges of raising capital and sourcing deals can make diversification difficult to achieve in practice. Limited partners may be hesitant to allocate significant funds to emerging markets, even if they offer more high-growth opportunities. And unless you have the brand recognition and network effects of a Y Combinator, generating the necessary deal flow for maximal diversification can be a tall order.

So, while the allure of capturing the tail-end outcomes through diversification is understandable, the realities of the venture capital landscape suggest that concentration may be the more pragmatic approach for most investors. By focusing on a smaller number of startups in which you have high conviction, you can allocate your limited resources more effectively and increase your chances of realizing outsized returns.

* I don’t mean strategy in the broad sense, encompassing aspects like market, geography, or cheque size. Here, I’m focusing specifically on the question of concentration versus diversification in your portfolio. How do you balance the potential benefits of spreading your bets against the need to build conviction in a select few startups? That’s the choice I wanted to explore in this section.

Ingredients - What factors shape your first impression?

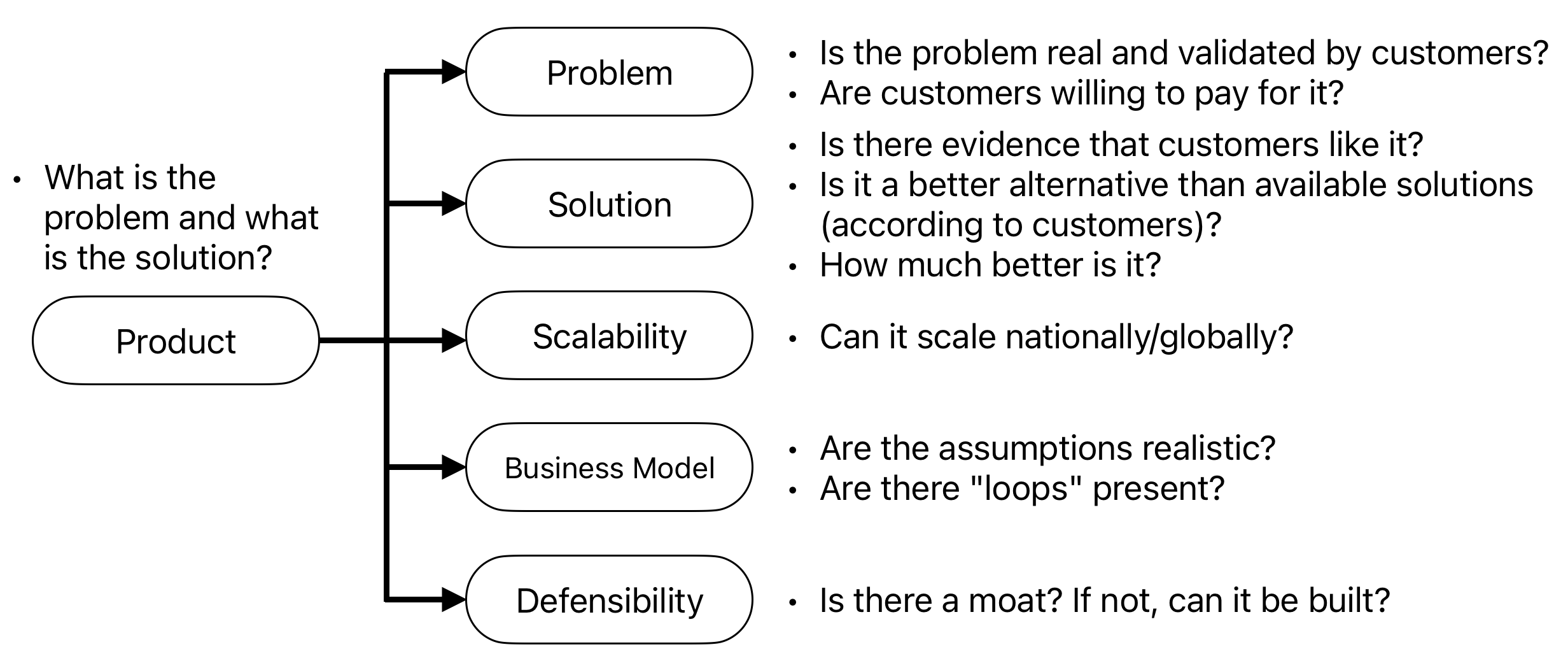

My goal here is to formulate first pass questions under the “big” buckets - Product, Market, Team, Risk/Reward. I’ve added Risk/Reward as a section because I think it’s crucial to explicitly consider the potential upside and downside of any investment, beyond just the merits of the product, market, and team. Also, I’ve expanded on a few sub-buckets to augment them with the wisdom of prolific practitioners. Admittedly, some of the grouping here is contrived, but offers rough heuristics to structure thinking.

Product

Business Model

From Byrne Hobart,

When you talk about companies, you probably use the term “business model.” Everyone knows roughly what it means. It’s the answer to three questions: What does the company do? What value does it produce? Why does it keep on existing?

But there are many ways to frame business models. Every one of them asks how a business reverses economic entropy and creates more value than it consumes (or at least does that for the people who could choose to shut it down). None of the models are wrong, but all of them are limited. And when one model stops working, it’s important to switch to the next.

…

All models are wrong, some models are useful. None of these models are perfectly descriptive. Every one of them breaks down in some situations. But every one of them can answer important questions about a business. These frameworks don’t provide answers, but they do help ask the right questions.

Emphasis mine. It’s interesting that Hobart flips the script on the applicability of business model frameworks within a mere ~2000 words. This underscores the effectiveness of relying on meta-models of business models rather than being beholden to the frameworks themselves. A business model is essentially a story about how a venture can make money, and the interpretation of this story is best left to the imagination of the listener, or in this case, the investor.

If this sounds a bit abstract, let’s take a look at a real-world example from the Southern Cone: MercadoLibre. Initially pitched as an eBay for Latin America, MercadoLibre has since evolved into a one-stop-shop for (almost) everything a merchant might need to fulfill transactions. Latin America is extremely underbanked, which acted as a bottleneck for MercadoLibre’s ambitions. To overcome this hurdle, they launched their own payment gateway, MercadoPago, enabling merchants and consumers to transact online without a bank account. Along the way, they expanded their offerings to include a credit arm, an asset management business, an online store solution, and an online listing service, all under one umbrella. So, what exactly is MercadoLibre’s business model? Is it an eBay, an Amazon, a Square, or a Shopify for Latin America?

Or perhaps an eBay + an Amazon + a Square + a Shopify for Latin America? This sort of reductivist projection is routinely overdone, but it’s valuable when it works.

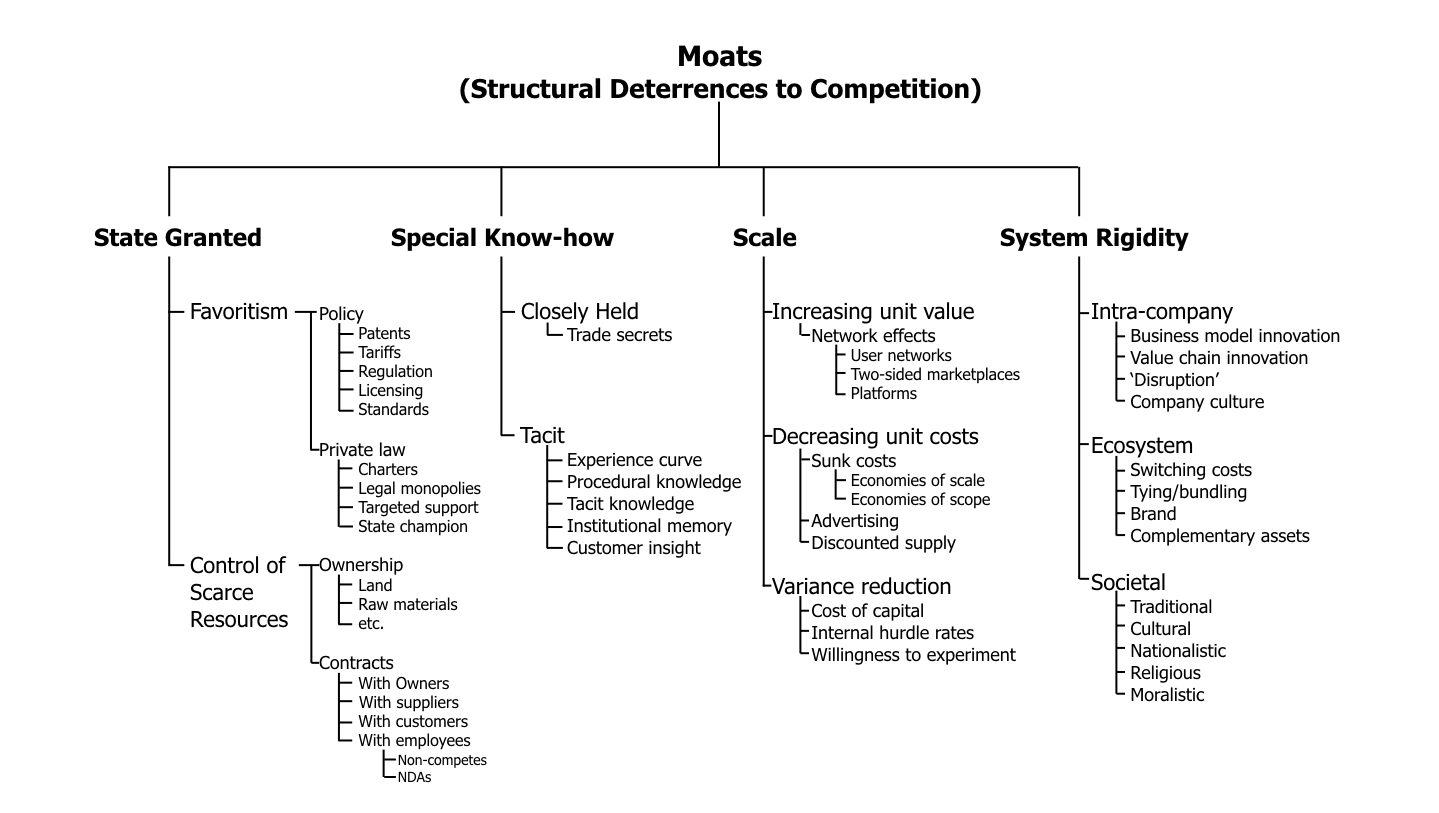

Defensibility

In many industries, companies seek competitive advantage primarily through innovation. The harder it is to imitate the innovation, the longer the startup has to reap rewards. Defensibility or colloquially, moat, is a measure of how hard it is to imitate a company’s offerings.

During the early stages, uncertainty is what protects startups from competition until a proper moat can be built, and so uncertainty becomes their moat. More often than not, it’s more helpful to think about moats the startup can potentially build in the future. Here we’ll take a quick look at structural causes for barriers to entry, excluding factors less likely to be imitated and not because they can’t be imitated but because it’s tough to: management talent, company culture, employee competence etc.

Source: Reaction Wheel

Source: Reaction Wheel

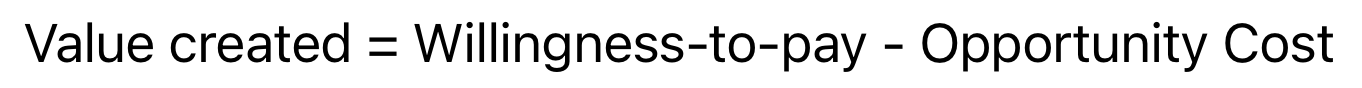

Now what? So you’ve identified potential areas of competitive advantage for the startup you’re evaluating. Now we can look into figuring out how the moat affects the customer’s Willingness-to-pay and the startup’s Willingness-to-sell or, orthodoxically, the Opportunity Cost of providing that product/service to the customer.

Adam Brandenburger and Harborne Stuart, professors of strategy, offer a simple and sound equation for how a firm adds value:

Source: “Value-Based Business Strategy,” Journal of Economics & Management Strategy, via Counterpoint Global

Source: “Value-Based Business Strategy,” Journal of Economics & Management Strategy, via Counterpoint Global

Felix Oberholzer-Gee, a professor of strategy at Harvard Business School, posits that companies should strive to increase willingness to pay and to lower willingness to supply, and this is how the economic pie, from suppliers to customers, grows.

Source: Based on Felix Oberholzer-Gee, Better, Simpler Strategy: A Value-Based Guide to Exceptional Performance, via Counterpoint Global

Source: Based on Felix Oberholzer-Gee, Better, Simpler Strategy: A Value-Based Guide to Exceptional Performance, via Counterpoint Global

Noting how a potential competitive advantage interacts with the value stick, visualizing how and where it expands and contracts, and benchmarking other players along the same stick paints a good picture of wide the moat is to keep the crocodiles at bay.

And now from the GOAT himself (emphasis mine):

What we refer to as a “moat” is what other people might call competitive advantage . . . It’s something that differentiates the company from its nearest competitors – either in service or low cost or taste or some other perceived virtue that the product possesses in the mind of the consumer versus the next best alternative . . . There are various kinds of moats. All economic moats are either widening or narrowing – even though you can’t see it.

Warren BuffetOutstanding Investor Digest, June 30, 1993

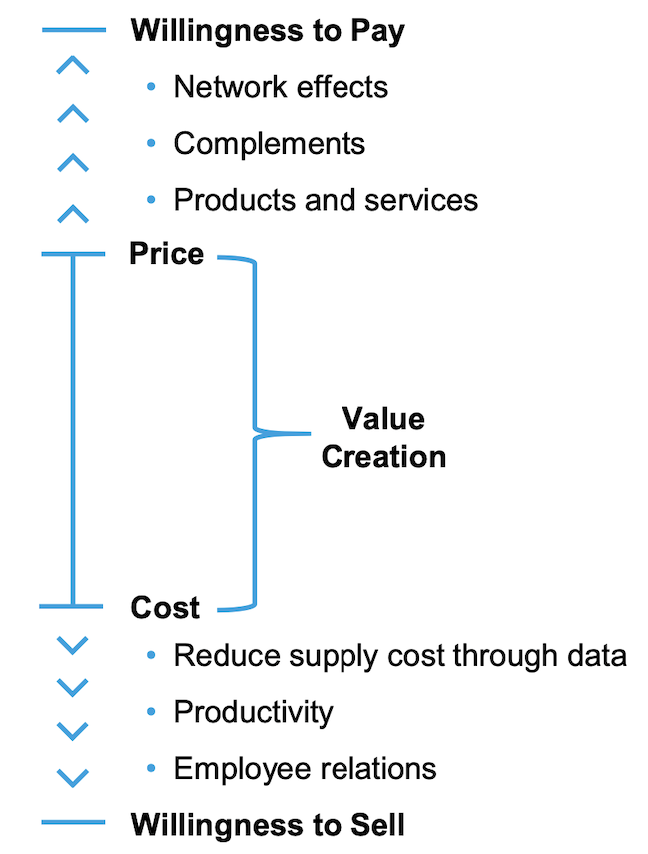

Market

Size

Michael Mauboussin notes a relatively underdiscussed aspect of market sizing in his 2015 paper on TAM:

[TAM is] the revenue a company could realize if it had 100 percent share of a market it could serve while creating shareholder value. You should recognize up front that TAM is not about how large a firm can grow to be but rather how much it can expand while adding value.

Emphasis mine. There’s a clear disclaimer that growth should not be pursued at any cost, particularly not at the cost of diminishing returns which could erode value for shareholders. In financial speak, growth should produce returns that exceed the cost of capital invested.

Webvan was one of those outlier companies that was almost anachronistic in it’s success and failure, and a classic example of a company that did not align its TAM with creating stakeholder value. Founded in 1996, online grocery retailer’s mission was to deliver grocery products to customers’ homes within a 30-minute window of their choosing. The company IPO’d at a valuation of more than $4.8bn during the dot-com bubble in 2001, and filed for bankruptcy less than 2 years later - the Y2K posterchild for “move fast, break things”.

Seemingly, the Webvan’s investors pressured it into growing very fast to obtain first mover advantage, serving as a good lesson on what not to do as an investor. The flip side case is what could pan out like Byju’s, with a valuation cut of ~86% in 15 months, and nearly all early backers quitting the board. I don’t know what the balance is, but I feel like bad faith actors could be spotted fairly early before large scale value destruction.

Maturity and Timing

When evaluating early-stage investments, it’s crucial to consider the maturity of the market itself. Early-stage investors accept that many, if not most, of their investments will fail. This risk is even greater when the market is in its early stages. While a significant portion of capital in these sectors may yield substandard returns, it plays a critical role in driving experimentation and product innovation.

An industrys evolution cycle follows a predictable cycle of boom and bust. It’s the next big thing for a hot minute, until the founder is jailed for 25 years. Studying the maturity of a market can help adjust a startup’s probability of success, beyond just evaluating the company’s own merits.

Source: Counterpoint Global

Source: Counterpoint Global

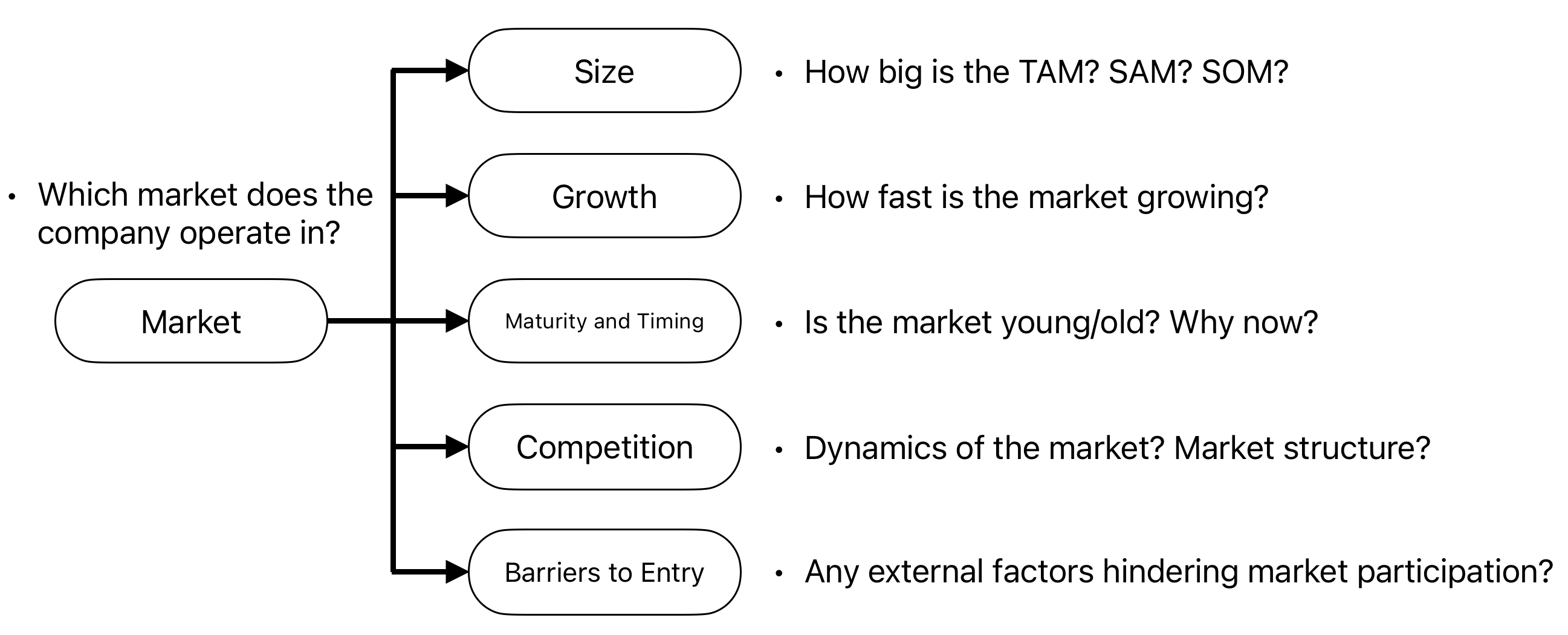

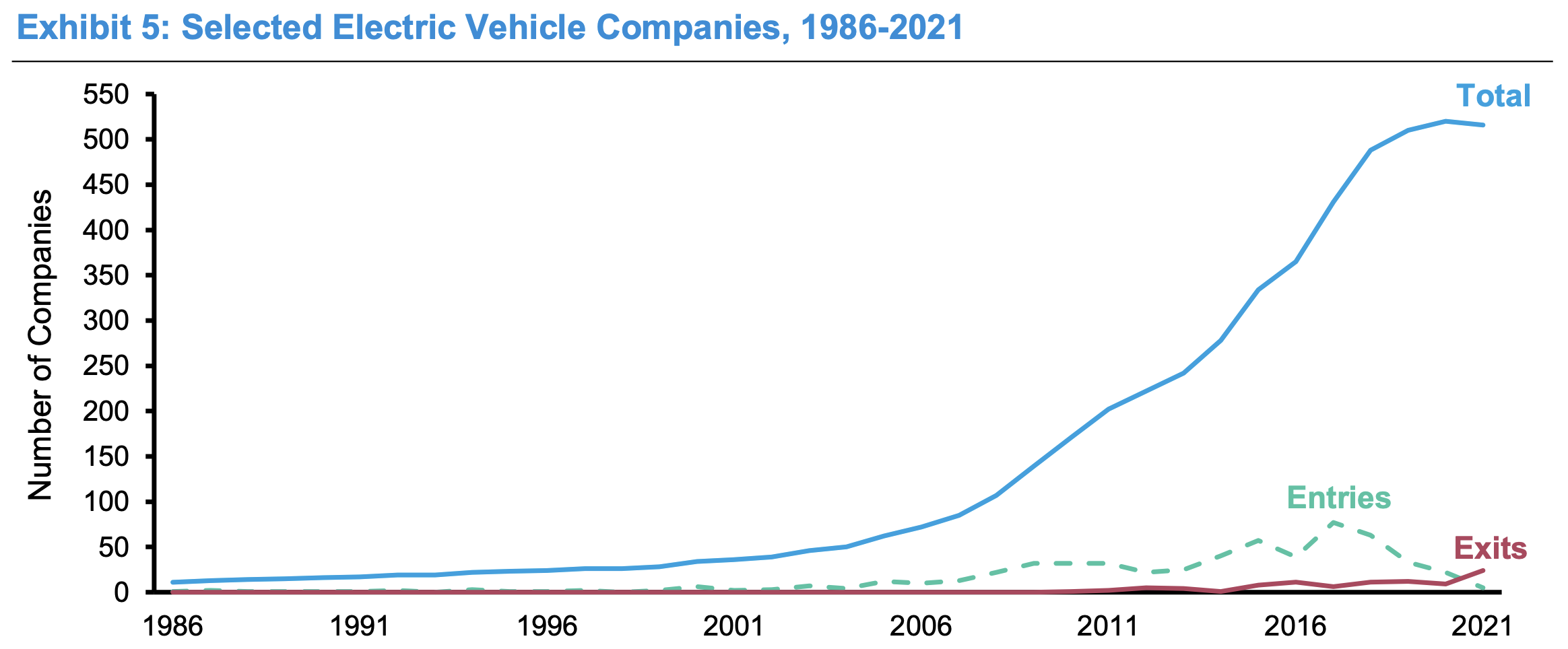

Consider the trajectory of a well-established industry such as the automotive sector. The auto industry, which began in approximately 1895, experienced a significant influx of new entrants until around 1910, and then from 1910 to 1941, the industry witnessed a considerable net outflow of companies exiting the market. On the other hand, the electric vehicles market stands in sharp contrast.

Source: Counterpoint Global

Source: Counterpoint Global

The EV industry looks to be on the cusp of the pruning process. Standards have been established, entrenched players command significant market share, and process innovation keeps the top companies ahead.

From Mauboussin, again:

Steven Klepper was an economist at Carnegie Mellon and a leader in this field. This pattern of boom and bust is known as the product life cycle. Klepper identified and described six regularities in this evolutionary process:

- As an industry is born it is common for the number of entrants to rise and then fall over time. The total number of competitors is ultimately small.

- The output of the industry continues to grow even as the number of producers falls from the peak.

- The market shares of the competitors are unstable at first, but eventually stabilize.

- The diversity of versions of competing products coincides with the growth of entrants. The number of innovations peaks in the growth phase and falls thereafter.

- Product innovation is the focus early in the cycle. Process innovation is the focus late in the cycle.

- When the number of entrants is on the upswing, most product innovations come from new entrants.

Klepper, along with Michael Gort, an economist, examined 46 industries and measured the average time it took to pass through the various stages, including the growth in net entry, low to zero net entry near the peak of competition, and negative net entry. The early phases last longer on average than the late ones. Further, we can observe that the diffusion of new innovations is happening faster today than it did in the past.

Trading off some fidelity, we can adopt at a few rules of thumb depending on the market stage. In a nascent market, prioritize startups innovating on the product. In a maturing market, process innovation becomes key. Adjust return expectations based on the inherent risks of the industry’s phase. By understanding where a market is in its life cycle, investors can make more informed decisions about which startups to back and when.

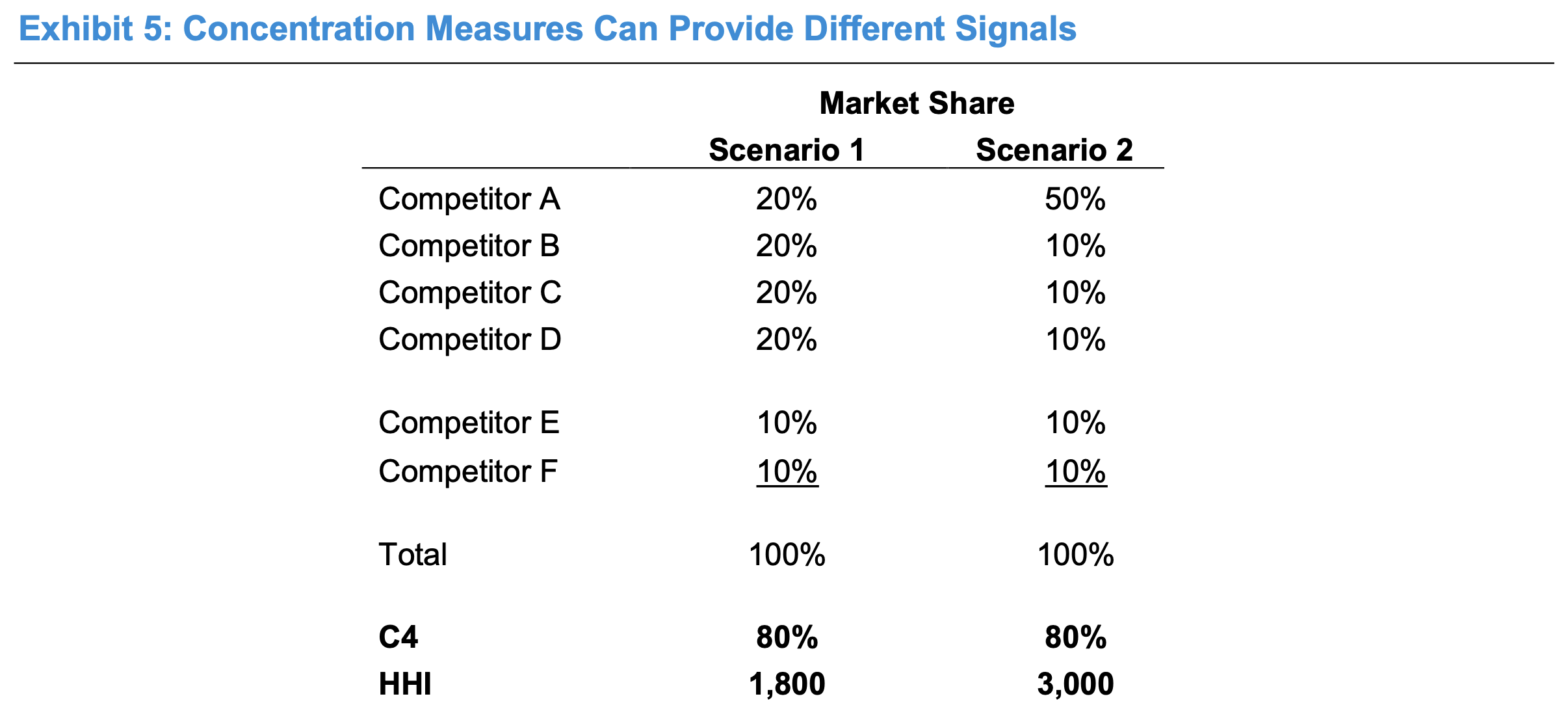

Competition

Industry concentration serves as a metric for assessing the number of firms in an industry and their relative influence. Industry concentration is a robust measure for gauging the intensity of competition, which in turn affects profitability. It’s a quick and easy pulse check of an industry. Although you’d be able to make out industry characteristics intuitively just by looking at competitor market shares, there are some quantitative methods we can employ.

One way to estimate industry concentration is the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI). The HHI considers not only the number of firms but also the distribution of the sizes of firms. A dominant firm in an otherwise fragmented industry may be able to impose discipline on others. In industries with several firms of similar size, rivalry tends to be intense. Many economists characterize readings in excess of 1,800 as industries with reduced rivalry.

Higher the index, the more monopolistic the industry.

Another popular measure is the C4 concentration calculation, which adds up the market shares of the largest four industry participants.

Source: Counterpoint Global

Source: Counterpoint Global

While in this example, both measures convey markedly different messages, in practice, these metrics generally come to the same conclusions.

These measures have their limitations, as market boundaries are often complex to define and the measures are not reliably linked to sustainable competitive advantage or stock returns, so as with anything, take them with a pinch of salt.

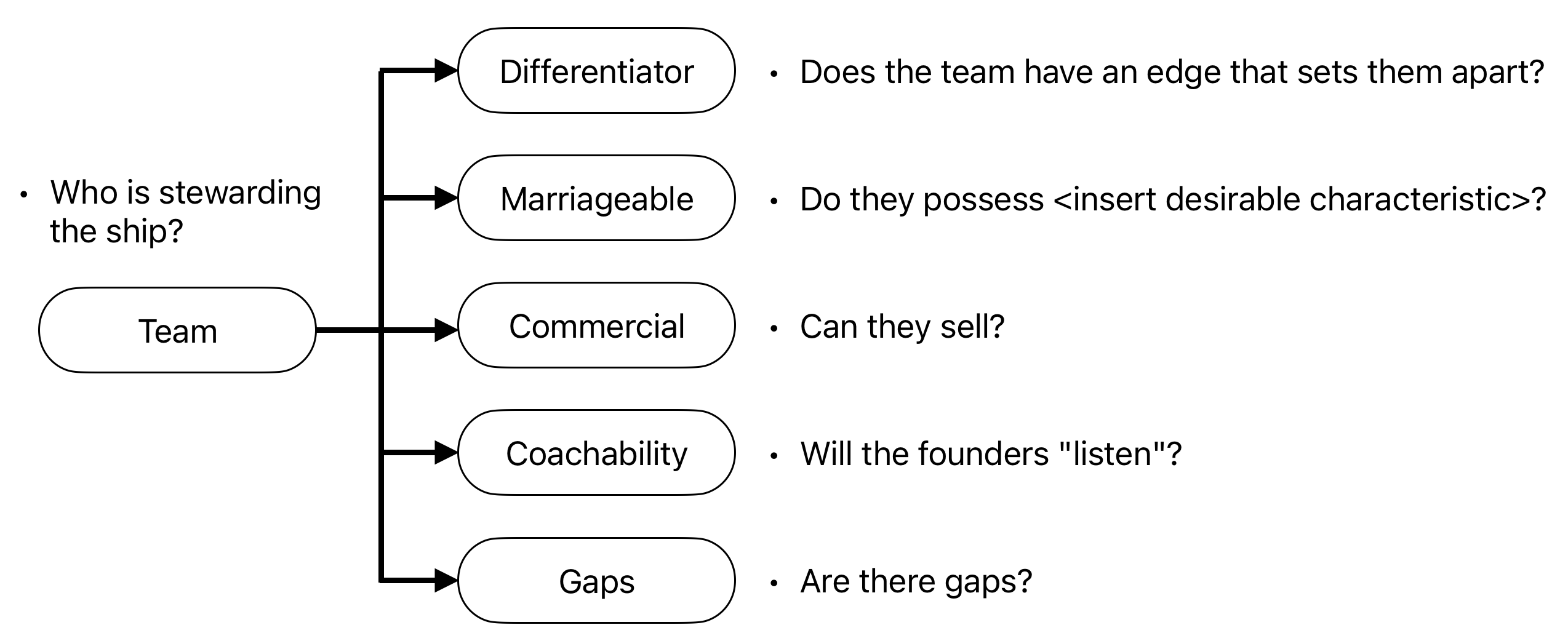

Team

While this is the most important area to focus on during due diligence, especially so at early stages, I don’t have much to say here. Most firms will have their own versions of enneagram tests to determine if their stars align with the founders they’re considering hitching their wagon to. And for good reason - this relationship will likely last several years, far longer than the average two-year stint most romantic partners sign up for.

I do want to hone in on coachability though, because I think it’s one of the trickier things to suss out. Founders absolutely need to listen to their customers, their employees, and their investors. And of that trio, investors have the most incentive to dole out honest, if sometimes harsh, feedback. As Jerry Neumann, adjunct professor at Columbia University, points out:

If you believe, as I do, that actively helping the companies you invest in increases their chances of success, then you have to balance the decreasing rate of growth in probability of reaching the benchmark against the number of companies you can actually help at any given time.

…

Remember, these are not balls being pulled from an urn, the distribution of outcomes arises from the system that exists, one that presumably includes the help of the financier: reducing that help may cause the system to perform worse.

I believe that helping increases the average outcome. Perhaps you question it. But you don’t have to believe very strongly that investing in too many companies decreases your outcomes to see that there is a point where the decline in outcomes offsets the very slow growth in the probability of a 5x.

In other words, investors need to strike a balance between diversifying their portfolio and being able to effectively support each company they back. Spreading yourself too thin can lead to diminishing returns, no matter how much you believe in your own Midas touch.

Research shows that investor-founder conflicts are often triggered by perceptions of unethical behavior, leading to finger-pointing and blame-games. A term sheet might be a marriage contract, but without coachability, even the most promising unions can end up in messy, drawn-out divorces. At the end of the day, you’re not just betting on a product or a market - you’re betting on a long-term relationship. And just like in marriage, communication and a willingness to work on yourself are key to going the distance.

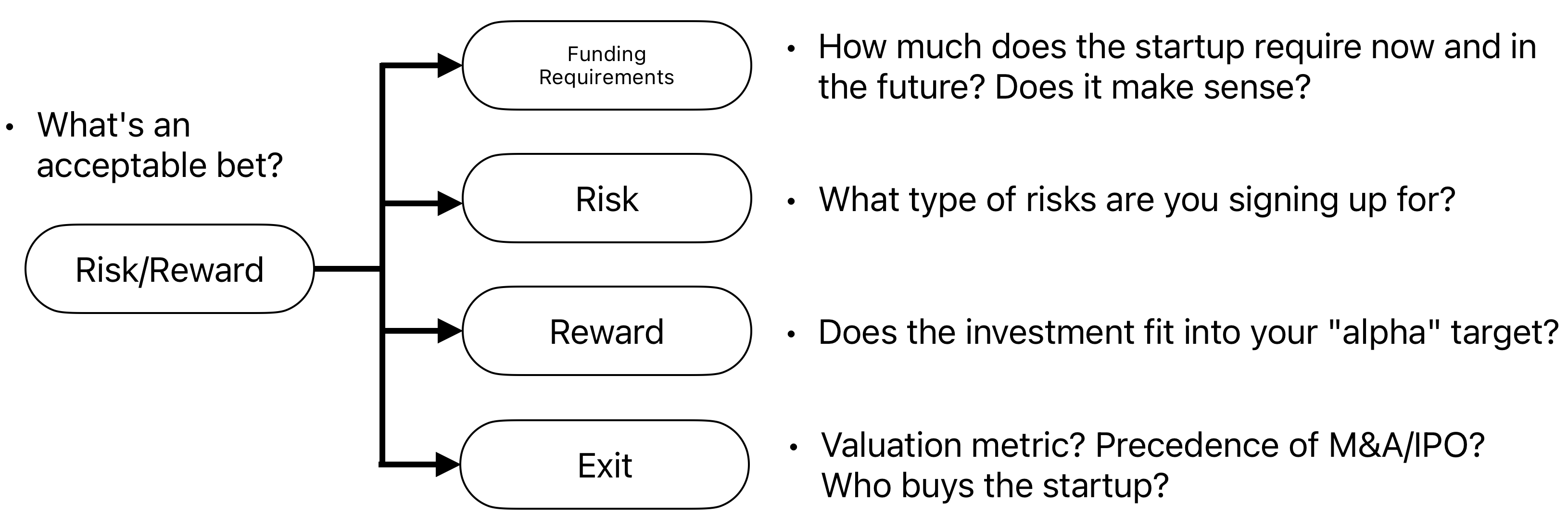

Risk and Reward

Funding Requirement

Besides validating the amount of funding the startup needs, sparing a quick thought on follow on funding required for pro rata exercise is helpful. Dan Lupoch has built an excellent tool to play around with and visualize equity dilution and stakeholder returns here: Venture Dealr. There’s tons of good content floating around on evaluating capital efficiency and the math of fundraising, so I’ll skip that for now.

As a cautionary reminder though, it’s helpful to remind yourself of the weight of your decisions when you’re dealing with other people’s money.

Source: X (then Twitter)

Source: X (then Twitter)

Risk

The risk-reward profile of a VC fund’s investment in a startup is similar to that of a (far) out-of-the-money (OTM) call option. You invest by purchasing equity at a certain price, hoping to exit when the share price is significantly higher. Crucially, you can increase the value of a call option by raising either the expected value of the underlying asset or its volatility. While the word volatility often carries a negative connotation, in the world of venture capital, it becomes a crucial lever for achieving outsized outcomes. Bold, ambitious bets are the expectation when the odds are stacked against you.

To put this into perspective, median deal size in the angel/seed stage is about $1.5mn and 3 out of 4 startups fail. Let’s assume the average early stage venture investment is ~$2mn for 10% of the business. If 75% of investments don’t meet targets, then to break even on a probability-weighted NPV basis, assuming a 0% IRR (i.e., no discount rate), the target exit (before dilution) would need to be $80mn. If the company undergoes two additional funding rounds, each resulting in a 20% dilution for existing shareholders, the break-even exit value shoots up by ~56%, reaching $125mn.

However, venture funds must target much higher return thresholds than a 0% IRR. For a 6-year exit timeline and a target IRR of 40%, assuming no dilution, the exit would need to be worth $472mn, nearly six times the 0% IRR scenario. Assuming a 10x revenue multiple, this still equates to a ~$47mn target run rate revenue. That’s a CAGR of nearly 127%!

Some economists think VCs should not adjust for the probability of failure and they should adjust their expectations of return for the companies they invest in and use a non-adjusted discount rate. Jerry Neumann flatly disagrees:

This argument is flawed: moving the numbers around in the spreadsheet does not change the amount the investor must receive from the companies that succeed. Since no one knows which companies will succeed and which will fail, the investor must expect the higher return from all of them.

Reward

(This section heavily borrows from Jerry Neumann’s excellent post on Power Laws in Venture — do check it out!)

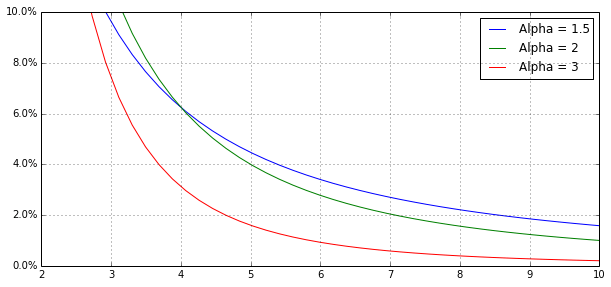

Popular convention holds that exit values obey the power law, which is, quite literally, characterized by \(\alpha\). Alpha defines the shape of the power law and determines how “fat” the tail is, as you can see below.

Source: Reaction Wheel

Source: Reaction Wheel

Power law distributions possess two interesting properties that normal distributions don’t: “fat” tails and no/infinite mean for alpha values under/equaling 2.

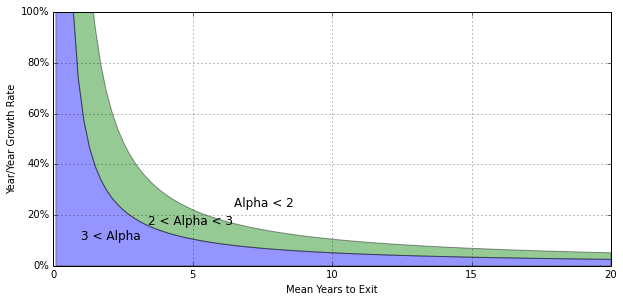

We can build a simplistic, first order approximation model for venture returns by building a power law distribution with \(\alpha = \frac{1}{gi}+1\), the probability of an exit value of \(x\) is:

\[p(X=x) = \frac{1}{gi}x^{-\left(\frac{1}{gi}+1\right)}\]where \(g\) is the year on year growth rate of the startup, and \(i\) is the average number of years to exit the investment.

Source: Reaction Wheel

Source: Reaction Wheel

Why would you prefer “fat” tails?

As \(\alpha\) gets smaller, or as the product of year on year growth rate and expected time to exit gets larger, the tail becomes fatter. Fatter tails indicate a higher probability of achieving outsized returns from their top-performing investments.

What does “infinite” average for the distribution mean?

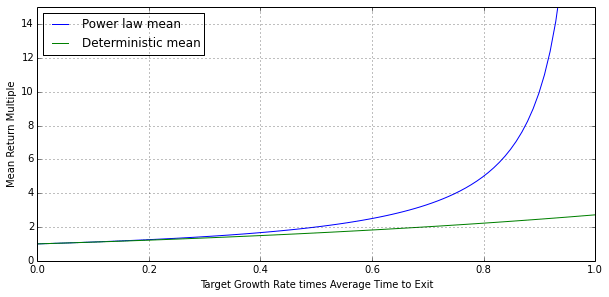

Mean of a power law distribution is (\(\alpha\) - 1)/(\(\alpha\) - 2). So you can imagine why funds want to be centered around 2. At \(\alpha <= 2\), the distribution average grows as you make more venture bets, with the largest value you are likely to get, scaling as per \(\langle x_{\max} \rangle \sim n^{\frac{1}{\alpha - 1}}\). And this pleasantly surprising upshot is what attracts investors.

Source: Reaction Wheel

Source: Reaction Wheel

This model implies that venture capitalists “choose” alpha as a primary driver of their strategy. Venture capital alphas typically cluster around 1.96, which gives us a return multiple target of ~3x (modeling return multiple, \(m\), as \(m = e^{gi}\) and plugging in \(\alpha = 1 + e^{\frac{1}{gi}}\), gives us \(m = e^{\frac{1}{\left(\alpha - 1\right)}}\)).

Lower alpha implies a higher target multiple. and measuring alpha of a fund distils out luck, focusing more on skill.

Exit

The exit landscape is witnessing an upheaval these days, with venture capital borrowing a tool or two from private equity. Recent macro challenges have made it difficult for funds to stick to the typical 8-10 year holding period. LPs are banging on their doors for returns. A timid IPO window, regulatory kerfuffles around M&A, and an increased focus on stock buybacks for private companies that have stayed private for a long time - it seems like both startups and their backers would like them to stay private for longer. Continuation vehicles (where funds transfer investments from the original vintage to another vehicle to hold it for a longer period) might be here to stay, blurring the lines between venture capital and private equity. This maelstrom of hurdles is forcing investors to re-evaluate their exit strategies and timelines.

Conclusion

A little further into our conversation from before:

…

Friend: You know what? I think there’s merit to exploring each facet here. But I trust the kid. And I feel like that’s worth taking a shot on.

Me: I guess that’s a good enough reason :)

In the end, the world abounds in Malthusianisms. Early stage investing is a risky business, and one can only hope to be proved wrong like Malthus was.

Further Reading

There’s a lot of good content available online, a bunch of which I used to inform my thinking. Linking to resources I haven’t already linked above here:

- Sequoia Capital - Writing a Business Plan

- Ada Ventures - A seed investing framework

- Tren Griffin’s writeup of Floodgate’s investment thesis

- Kevin Kwok’s thinking on loops

- USV’s Thesis 3.0

- Madrona Venture Group

Disclaimer: This post is a long note to myself, and there’s probably a lot of inconsistencies here. My thinking is shaped from being privy to funding deals as an enabler rather than a decision maker. Please qualify every strongly stated opinion here with some flavour of “I think”/”I believe”/”In my opinion”. Caveat emptor!